E-Commerce Warehouses Are Springing Leaks

A favorite pandemic property bet faces tougher times now that a boom in online shopping is waning, but still offers shelter for long-term investors

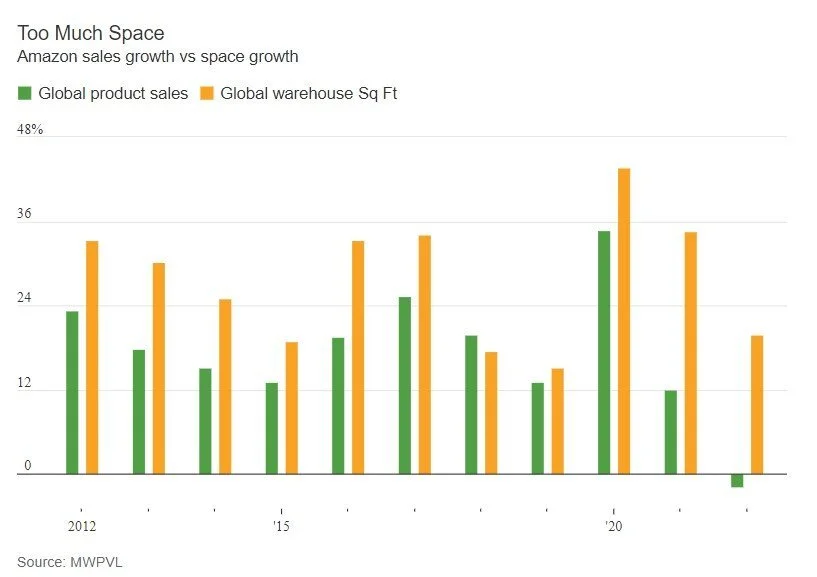

Amazon said earlier this year that it almost doubled its U.S. warehouse footprint in two years.

People are taking a breather from online shopping. Amazon.com AMZN -1.85%▼ is the most visible victim, but the vast warehouse ecosystem that has sprouted to serve it could be hit too.

Consumers have gone back to buying goods in stores, which is slowing the blistering growth in e-commerce seen during the pandemic. U.S. sales in brick and mortar shops have grown faster than online purchases for four consecutive quarters, real-estate research house Green Street points out. Several European online-only retailers, including fashion website Zalando and furniture brand Made.com, have issued profit warnings in recent weeks, following a sudden drop in demand.

Amazon said earlier this year that it overexpanded during the pandemic, almost doubling its U.S. warehouse footprint in two years. Since then, it has closed or canceled the opening of 28 delivery hubs or fulfillment centers in the U.S. and delayed the opening of another 15 to save on labor costs, based on data from supply chain consulting firm MWPVL International, which is tracking the rejig.

Amazon was responsible for around 15% of net absorption of industrial space in the U.S. last year, so warehouse stocks inevitably took a hit. Prologis, one of the most valuable commercial real-estate stocks in the world, has fallen 25% since the beginning of the year, underperforming wider commercial real-estate indexes like the EPRA Nareit USA index, which has dropped almost a fifth. U.K.-based Segro is down 26%.

But as consumers spend less time online and buy fewer discretionary goods in response to inflation, CEOs may grow cautious about taking on new space. Green Street estimates that European e-commerce sales will grow 11% a year between now and 2025, down from an earlier estimate of 14%. It expects U.S. online sales to grow by 7% annually over the same period. This means e-commerce tenants will have a lower share of new leasing activity, a trend already evident in Prologis’s results.

Still, contrarian investors may see a case for buying the dip in warehouse stocks. Online sales will still outgrow store purchases over the longer term. And while some generalist retailers such as Target are carrying too much inventory today, others will need more warehouse space to offset risks in the global supply chain.

High transport costs may also support demand for warehouses close to population centers, as it becomes increasingly expensive to haul goods over long distances. Transport bills account for around 50% to 70% of total logistics spend, whereas costs for fixed facilities including real estate are up to 6%, CBRE Supply Chain Advisory data shows.

Warehouse owners didn’t fare well in previous economic downturns. Distribution hubs are some of the fastest types of commercial real estate to build, so supply can quickly swamp demand in a recession. Yet vacancy rates today are much lower than before the dot-com bust and global financial crisis. In the U.S., under 5% of industrial real estate is empty, compared with 10% in 2007. The figure is even lower in Europe.

The wider e-commerce slowdown isn’t impacting leasing activity yet. Prologis reported strong second-quarter results this week and expects market rents to increase by 23% globally in 2022. Occupancy rates in the company’s warehouses are almost 98%, and 71% of leases that are expiring over the next year are either pre-let or in negotiations—well above the company’s prepandemic average.

Full Story on wsj.com >