A Red-Hot Market for Warehouse Workers Has Cooled Off

Companies say an era of rising pay and signing bonuses in one of the economy’s strongest hiring sectors is over. ‘It got bananas.’

Josh Marshall says he could use two more workers on his team in the warehouse operations of a Bayer seed-production facility in central Illinois, but the company isn’t rushing to raise wages or take other steps to speed along the hiring.

“We’re just at the point where we’re willing to wait it out,” said Marshall, who operates a forklift at the facility. “We’ve got enough people to kind of get by.”

A warehouse hiring spree that made logistics one of the fastest-growing job sectors during the pandemic, as businesses added nearly 700,000 workers in just over two years, is over. PHOTO: ROGER KISBY/BLOOMBERG NEWS

That is a big change from the past three years, when fierce competition for warehouse workers triggered higher starting salaries, hiring bonuses and extra rewards for attendance, with some sites even draping banners across their distribution centers to lure new recruits.

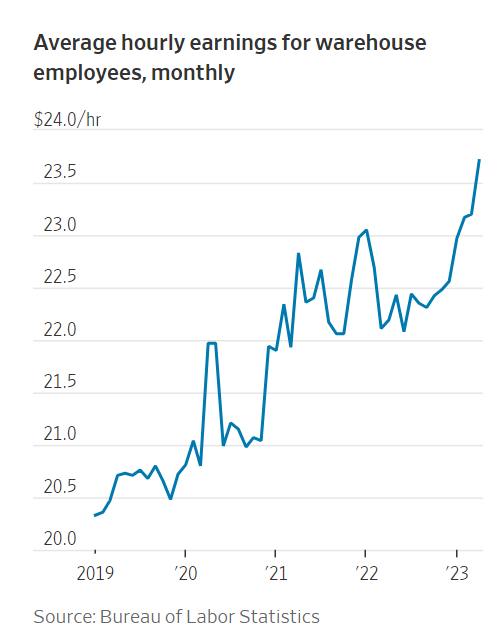

A warehouse hiring spree that made logistics one of the fastest-growing job sectors during the pandemic, as businesses added nearly 700,000 workers in just over two years and increased average hourly pay about 8%, is over. A looser U.S. labor market, a pullback in the growth of online sales and broader economic uncertainty have left many companies choosing to stand pat on hiring as demand for warehousing and logistics services retreats from historic high levels.

“It got bananas,” said Dawn Nixon, senior vice president of human resources for the Americas and Asia Pacific at contract-logistics provider GXO Logistics. “I think every employer dealt with people that would leave our warehouse and go to the warehouse down the street for 25 cents more an hour.”

U.S. warehousing employment hit a peak of 1.96 million jobs in June 2022, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since then, the sector has shed more than 41,000 jobs, according to the BLS seasonally-adjusted figures.

Although the number of workers handling goods at warehouses and picking and packing online orders at fulfillment centers is still nearly 275,000 jobs ahead of the level of two years ago, by the BLS measures, companies say the urgency to hire and to replace workers who leave their jobs has dimmed.

“The leverage really felt like it was in the hands of the warehouse employee over the last two and a half or three years, until really the beginning of this year,” said John Merris, chief executive of Grapevine, Texas-based Solo Brands, which owns portable stove maker Solo Stove and men’s apparel seller Chubbies.

Merris said his company offered attendance bonuses in 2021 and 2022 to help retain workers during the critical end-of-year peak season. Merris said he would decide later this year if he’ll repeat that but says the market is very different now.

“This year it started turning to where it felt like there was enough availability that we weren’t feeling a pinch around being able to find good workers, quality workers, in the warehouse at the wages that we offer,” he said.

Figures suggest the broader U.S. jobs market has remained strong even in the face of rising interest rates and relatively modest economic growth. Workers gained more than 1.5 million jobs in the first five months of the year, boosted in part by resilient consumer spending.

But growth in household spending in May came largely because Americans spent more on services and less on goods, which drive business through distribution and warehousing networks. E-commerce sales, which peaked at 16.5% of overall U.S. retail sales in the middle of 2020, retreated to 15.1% of the market by this year’s first quarter.

Retailers and logistics operators have pulled back on supply-chain investments in response in recent months, including closing some warehouses and cutting jobs.

Executives say they expect the impact of the labor crunch to linger in company finances, however. The average hourly wage for a warehouse worker in the U.S. was $23.71 in April, up about 8% compared with May 2020, according to BLS data.

Nixon of GXO said the Greenwich, Conn.-based company today pays warehouse workers about $20 to $24 an hour depending on location, up from about $14 to $18 an hour before the pandemic.

“I don’t think that these wages are going to roll back anytime soon,” Nixon said.