Canadian Government Pushing for Foreign Entrants and Online Innovation in the Grocery Sector

Canada's grocery business doesn't have enough competition — and shoppers are paying the price, report finds.

Report is the results of months-long probe by competition watchdog

Loblaw, Empire/Sobeys, and Metro hold the reins as dominant grocers in the Canadian grocery market. Although these companies are well-managed, the Competition Bureau’s recent report highlights some of their practices aimed at maintaining market dominance. One notable aspect of the report is the endorsement of the Grocer Code of Conduct.

Canada's grocery business is controlled by large players and needs government assistance to encourage new entrants to bring down prices, a report from the Competition Bureau says.

The report, published Tuesday, is the result of a probe that Canada's top competition watchdog launched last year, when concern over food prices hit a fever pitch.

The bureau spent months examining many aspects of Canada's grocery business, which is dominated by three domestic giants — Loblaws, Metro and Sobeys owner Empire — along with foreign players like Walmart and Costco.

Together, those 5 companies combine for more than three-quarters of all the food sales in Canada.

In the report, the bureau found the industry is not as competitive as it could be, and consumers are paying the price for it.

"Canada needs solutions to help bring grocery prices in check," the bureau said. "More competition is a key part of the answer."

To that end, the bureau recommended four broad policies aimed at spurring competition in the sector. They are:

To establish a Grocery Innovation Strategy aimed at supporting the creation of new types of grocery businesses, specifically ones that only sell online.

Policies from all levels of government to encourage new independent and international players to set up shop in Canada.

Introducing legislation to mandate harmonized unit pricing requirements, which will make it easier for consumers to comparison-shop for deals.

Limit property controls, which currently restrict how real estate can be used by competing grocers, making it difficult, or even impossible, for new stores to open.

"Change will take time," the bureau said. "These solutions will not bring Canadians' grocery bills down immediately. But by acting now, governments at all levels can take steps toward creating a more competitive grocery industry in Canada."

The bureau's study found that while most countries are currently grappling with high prices for groceries, it's a different situation in Canada because the market is more consolidated than it is elsewhere.

A big problem is that in Canada, the main chains own discount rivals more than they do elsewhere.

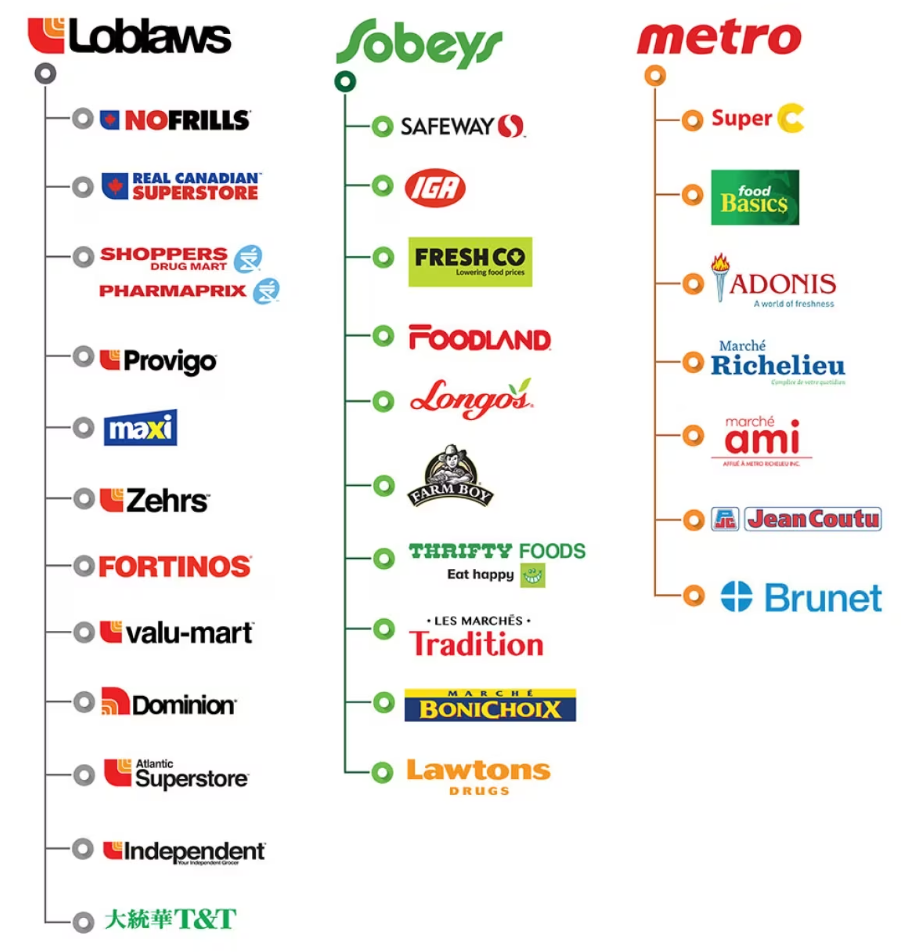

"Loblaws owns No Frills and Maxi, Sobeys owns FreshCo, and Metro owns Food Basics and Super C," the bureau said. "This is different from other countries where large grocers compete against lower-priced options, like Aldi and Lidl."

Canada's three big grocery chains own a slew of brands up and down the value chain. (Competition Bureau)

Big chains have unfair advantages

Independent grocery chains are often a great alternative, but they don't take up as big a portion of the market as they do elsewhere, the bureau said. That's because many of them are forced to buy their wares from the big chains in the first place.

"According to independents, this dependency makes it more difficult for them to compete on price," the bureau said.

Large chains also get paid by suppliers to put their products on shelves in the first place.

"Independent stores generally aren't, and that can put them at a disadvantage," the bureau said.

Even finding real estate to open a new store can be a challenge, because they generally need a large, accessible space with the capacity for parking.

"Many of the locations that could support a new grocery store are already controlled by the grocery giants," the report found. Known as restricted covenants in contracts like leases, such clauses can hinder competition by making it impossible for someone else to use the space to open a grocery store, even if the original grocery store closes down.

While the bureau's report covered a lot of ground, it was limited in its scope in that by design it did not delve into some parts of the grocery supply chain that might contribute to higher prices — specifically the relationship between retail stores and their suppliers.

"We did not set out to explain or understand all the reasons why grocery prices have increased," said Anthony Durocher, deputy commissioner at the bureau.

It was also limited in that ultimately, the bureau doesn't have the power to force companies to disclose information.

"While many grocers were happy to speak with us, others were more reluctant to share information," the bureau said. "This limited our ability to fully answer some questions that are top of mind for Canadians."

That's mostly because unlike many of its international counterparts, "the Competition Bureau does not have formal power to compel information from market participants."

Foreign discount chains weigh in

While some Canadian chains may have been reticent to talk, the bureau said it heard opinions from a number of international grocery chains for their views on the Canadian market.

"We were told that while Canada is an interesting market, entry could be challenging," Durocher said. "Some international players view the Canadian market as tough to break into given the strength of the domestic large chains."

German grocers Aldi and Lidl are aggressively growing their U.S. footprint and helping to lower food prices. Aldi has locations across Europe, China, Australia and the U.S. but none in Canada.

The Retail Council of Canada, which speaks on behalf of Canada's big grocery chains, says the reluctance of foreign discount chains like Aldi and Lidl to open up shop in Canada speaks to how competitive the market already is.

"Basically they said ... it's a fiercely competitive market already and went further to say ... 'I'm not sure we could compete on price,'" spokesperson Karl Littler said in an interview.

Overall, Littler says the bureau's report is "further evidence against the greedflation smear that we faced." That's a reference to allegations that major chains were unduly profiting from inflation by raising prices more than their costs had increased, something the industry has repeatedly denied.

"There was a lot of hysteria about this," Littler said, noting that even the bureau found the industry to have "modest profit levels, not the excess that some have alleged."

While the industry says there is fierce competition between the major players, Keldon Bester, a competition expert and co-founder of the Canadian Anti-Monopoly Project, says it's clear that Canada's grocery business is not as competitive as it could be.

"The waves of consolidation that we've allowed to happen have really reduced the diversity and dynamism of grocery markets for Canadians, especially in rural areas," he told CBC News in an interview. A former staffer at the bureau himself, he says he sympathizes with their plight because, "our law doesn't really set them up for success by not taking these mergers seriously," but says "the first step is stopping the further consolidation of markets that we know aren't delivering as much benefit as they could be."

The bureau noted that the level of competition in Canada very much depends on where you live, as big cities generally have a lot more options for shoppers, whereas remote and rural communities are often beholden to whatever stores are available.

Shopping at one of the major chains in Calgary recently, shoppers told CBC News that while they felt like they had plenty of options, they doubted that new players would be able to do much to bring down prices.

"Right now, I find in the flyers, they're all the same," said Mary Januszczak. "Everybody's copying each other — these guys have the same price as Safeway, Save-On [has] the same price." "It used to be … somebody would have something better on sale, and you'd go over there. Now everybody's the same."

If a new store were to open, Januszczak said it would take a lot for her to go there, due to the convenience factor of her current store. "Even if they're cheaper, I'd spend more money on gas to get there."

Shopping at the same store, Kalvin Lau said he doubted there is much that can be done about higher prices.

"As long as the grocery chains dominate the market, I don't think there will be huge change," he said.

A push to bring more competition into the Canadian grocery sector in the form of discount European brands such as Aldi and Lidl would face steep obstacles in Canada’s fragmented marketplace, experts say.

The Competition Bureau’s probe into concentration among Canada’s grocers released Tuesday highlighted the role international competitors could play in lowering prices as food inflation continues to cause pain at the grocery store.

The report argued that introducing international grocers such as Aldi and Lidl would push the dominant incumbents — namely Loblaw, Metro and Empire — to lower prices to compete with the discount brands popular in Europe and some parts of the United States.

The Bureau drew on a 2008 report that showed the so-called “Aldi effect” drove down grocery prices in Australia when the retailer entered the country, and even used Canada’s experience with Walmart as an example to show how a new player can disrupt the status quo.

A Reuters report from 2008 shows a move from Walmart to cut prices on food staples by as much as 35 per cent put pressure on competitors to do the same; a 2015 Bank of Canada study showed that the company’s innovative cost structures were driving down prices elsewhere in the sector.

“There is such a thing as the Walmart effect,” says Sylvain Charlebois, director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University.

“When a new store opens, prices tend to drop — including food prices. That’s why I think everyone wants the ‘Aldi effect’ to come into the market to see this new wave of deflation with food prices.”

Of all the recommendations made in the Competition Bureau’s report, it said attracting international grocers “may be the best option” to boost consumer choice and improve prices for Canadians.

Bringing in new players easier said than done

If the likes of Aldi and Lidl could shake up Canada’s grocery sector and compete aggressively with established players, the obvious question is: Why haven’t they?

The Competition Bureau’s analysis included interviews with international grocers to get their take on challenges entering the Canadian market.

Some of the barriers are physical: Canada’s expansive geography and low population density make it hard to set up operations efficiently, the report noted.

But beyond that, the Bureau found that the country’s existing grocery giants are “daunting competitors” to outsiders. Without naming names, the report said that one international grocer said it believed it could compete on price with the incumbents, while another said the task would be “difficult.”

The report hinted that in the Competition Bureau’s conversations with international grocers, some players said they were studying or had studied the prospect of expanding into Canada, but none had formally announced plans to do so.

Global News reached out to Aldi and Lidl for comment on Wednesday but did not hear back.

Canadian laws and tastes come with a number of standards that can be difficult for new entrants to get up to speed on. Labels on packaging need to be bilingual, for instance, and the Competition Bureau report notes that catering to multicultural Canadian consumers would mean carrying a wider array of ethnic products than they might otherwise sell in their home markets.

Charlebois says that interprovincial trade barriers and other government red tape can be a significant headache for international players. Launching as a truly national brand is difficult because, from province to province, there are different labour laws and regulations to consider, he says.

“All these little rules cost more money,” Charlebois says.

He argues that established companies have already baked the costs of operating in Canada into their business models — the country’s carbon pricing regime, for one — but the country’s unique federalism system requires a complex strategy for a new player to find success.

The Competition Bureau report highlights Target’s failed entry into the market, whereby it bought up Zellers outlets in a major push only to pull out mere months later, as a possible warning sign to international players thinking of a similar move.

Charlebois says Target is not the only casualty of an inhospitable retail landscape in Canada.

“Target really miserably failed in 2014-15 just because they underestimated the complexities of the Canadian market,” he says. “We lost Lowes, Sears. We just lost Nordstrom. So if you want a national player, it is extremely difficult.”

When Walmart entered the Canadian market in 1994, it did so via the acquisition of Woolco. It started with a relatively small footprint and built up its brand over time to adapt to the Canadian market, Charlebois says.

While that slow-and-steady strategy might’ve worked decades ago, he expects dipping an international brand dipping its toe into a market like Toronto or Vancouver would not work as well today. Fresh competitors have to go “fast” in the food sector these days, or the existing “regime” would mobilize to limit their business prospects.

A spokesperson for the Retail Council of Canada, which represents the country’s major grocers in the industry, said in response to the Competition Bureau report on Tuesday that the grocery market has “always welcomed competition.”

Spokesperson Michelle Wasylyshen said in a statement that Canada’s grocers do not impose barriers on new entrants and instead said their absence was a sign that existing discount grocers are “well-established” in the market.

Michael von Massow, food economist with the University of Guelph, says that if international grocers don’t want to enter the Canadian marketplace, perhaps it’s a sign that Canada wouldn’t benefit from having them.

“If competitors are telling us they don’t want to come in, perhaps it means we have an already relatively competitive marketplace,” he tells Global News.

The Bureau noted as well in its report that Aldi and Lidl operate as the primary discount retailers in markets where they challenge large brands — in Canada; however, many discount options such as Food Basics and No Frills are also owned by the existing giants.

How can Canada attract outside players?

While the Competition Bureau report recommended governments “take steps” to encourage global players to enter the Canadian grocery sector, it was light on suggestions for what exactly that would look like.

Von Massow says he’d like to see a more direct study of the impact new grocers coming to Canada would have before governments go out of their way to attract international players with subsidies, as it has done recently to lure auto giants such as Volkswagen and Stellantis.

Help with some of the high overhead costs that come with expanding into Canada could lower the barrier to entry, but he says it’s worth being sure consumers will feel the benefit on their grocery bills at the end of the day.

“Should the government be saying, ‘Well, we’ll grease the wheels like we have for electric battery plants and that sort of thing?’ Government could do that, but I wouldn’t do it unless I had some real assurances that it would actually lower prices,” von Massow says.

Global News asked Industry Minister Francois Philippe-Champagne whether the government would take a similar tact to attract international grocers to Canada, or what other actions it would take in response to the Competition Bureau’s report.

A spokesperson for the minister did not say whether subsidies of any kind were on the table or if Ottawa would attempt to lure more international grocers to the market. The statement called the Competition Bureau analysis a “good first step,” adding the government will now review the recommendations to see “how we can continue to make life more affordable for Canadians.”

Charlebois says there are arguments for using government subsidies to lure manufacturers, as Kraft-Heinz received for a plant in Quebec, but not for bringing in retailers.

Rather, he’d like to see governments at all levels focus on improving market conditions for prospective entrants.

Even at the city council level, Charlebois says, there are zoning restrictions and conditions granted to grocers that will limit property uses in an area to box out competition. The Competition Bureau also flagged such property controls as a barrier to competition in the market.

But Charlebois also points the finger at the Competition Bureau, arguing its policing of the industry “devalues” Canada’s reputation as a good place to do business.

Executives at international grocers are reading headlines in Canada too, he says, and can see the relatively muted fallout from the Bureau’s investigation of the bread price-fixing scandal. Canada Bread was fined $50 million last week for its role in fixing prices, a penalty that came more than a decade after the initial incidents.

Weston Foods and Loblaw Cos. Ltd., both subsidiaries of George Weston Ltd. at the time, had previously admitted their participation in an “industry-wide price-fixing arrangement” involving the coordination of retail and wholesale bread prices. The investigation continues into other players in the industry.

Charlebois argues that if Canada is not seen to be taking collusion seriously — granting Loblaw immunity for its cooperation rather than prosecution, for example — why would an outsider try to break into the market when it knows it’s not part of the existing “regime”?

“Why would you go into a market where there are suspicions of collusion when you are not part of the family?” he asks. “It probably is getting some Aldis and Lidls to think twice about the Canadian market.”

Global News reached out to the Competition Bureau to ask whether it felt its response to the price-fixing scandal has affected Canada’s reputation.

Noting that the $50-million fine against Canada Bread was the largest price-fixing fine ever issued by Canadian courts, a spokesperson for the Bureau said that its investigations into the grocery industry have been “rigorous.”

Spokesperson John Power added that “price-fixing conspiracies are difficult to uncover” and can take longer to build the case so it can be proven in court.

Power said the grocery industry is becoming “more consolidated over time” and said Canadian laws “need to be modernized” so the Bureau can protect and promote competition.

“The Bureau continues to do everything in its power to pursue those who conspire to increase the cost of living for Canadians by fixing prices,” the statement read.

In the report, the Bureau said it also needs to approach its work in the grocery industry with “heightened vigilance and scrutiny” to ensure Canadians benefit from greater choice and more affordable groceries.

“We need to thoroughly and quickly investigate allegations of wrongdoing, and we need the power to act when issues arise,” the study said.

International Retailers Such As Aldi And Lidl Might Not Enter Canada Because Of Local “Price-Fixing And Manipulative” Grocers [Op-Ed]

By Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is Senior Director of the Agri-Foods Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University in Halifax.

According to the Competition Bureau, Canadian grocery shoppers require additional foreign players like Aldi and Lidl to lower food prices in Canada. But one may wonder why a foreign grocer would choose to invest in Canada, given the presence of an exclusive club of price-fixing executives who have manipulated market conditions for years with impunity.”

The Competition Bureau’s call for increased competition in the Canadian grocery sector is stating the obvious. Canada is home to numerous oligopolies that dominate various industries, with only a few companies holding significant market share. In the grocery sector specifically, five major players control nearly 80 percent of the food retail market. While some oligopolies function more effectively than others, their success depends on the companies behaving ethically, which is precisely the issue plaguing the grocery sector in Canada.

Loblaw, Empire/Sobeys, and Metro hold the reins as dominant grocers in the market. Although these companies are well-managed, the Competition Bureau’s recent report highlights some of their practices aimed at maintaining market dominance. One notable aspect of the report is the endorsement of the Grocer Code of Conduct. While the Code itself is not directly related to the Bureau, it significantly contributes to enhancing competition. By providing a platform to address supply chain disputes, the Code serves as a necessary disciplinary measure against grocers who abuse their market power, granting food manufacturers more influence. Consequently, independent grocers gain access to a wider range of products and increased protection. Ultimately, the Code offers consumers more choices and potentially more stable retail prices, making it a positive development worth applauding.

Additionally, the report emphasizes the need for all levels of government to participate in making the food market in Canada more competitive. This point cannot be stressed enough. Many consumers are unaware of how territorial grocers can be when expanding into small cities and towns across the country. They may acquire plots of land to prevent competitors from opening stores nearby, and shopping mall leases may include terms that restrict the operation of other food retail outlets. While seemingly insignificant to city councils and mall managers, these measures can have a considerable impact on market prices. In contrast to the United States, where the intricacies of mergers, acquisitions, and their effects on consumers are closely scrutinized, Canada lacks a similar level of attention to such matters. This discrepancy needs to be addressed.

The report suggests that Canada should tackle interprovincial barriers to attract external players like Aldi and Lidl, two German-based grocers that have already been operating in the United States for several years. The ways, means, and locations for selling food products vary significantly between provinces, and labour laws also differ. When Walmart entered the Canadian market in 1994, it faced challenges and made mistakes along the way. Walmart Canada now has over 400 stores across the country, but it took years. On the other hand, Target’s entrance into the Canadian market in 2014 failed miserably due to the intricacies of our market, and this experience has served as a lesson for many companies worldwide, including Aldi and Lidl.

Entering the United States is considerably easier, even for Canadian businesses. This fact is exemplified by Canada’s own T&T, operated by Loblaw, which is currently expanding into the American market where competition is even more intense. Greater opportunities, less bureaucracy, and a more flexible fiscal regime contribute to this favorable environment. However, the most significant aspect is America’s clear understanding of competition as a concept, with an unwavering commitment to eliminating monopolies and oligopolies. Americans view competition as an essential aspect of the market and are vehemently opposed to excessive consolidation, philosophically.

In Canada, too much competition can indeed become an issue. Our love-hate relationship with the concept has resulted in the establishment of crown corporations and “legal cartels” in various sectors, including dairy, eggs, poultry, and maple syrup, to name a few. We have grown accustomed to these marketing mechanisms, at least until prices become a problem for consumers. At that point, we expect the government to intervene. This conflicting attitude towards competition poses one of the greatest challenges for the Competition Bureau.

The desire for increased competition and the attraction of more players to the grocery sector necessitate that the Competition Bureau takes effective action. The food industry is currently grappling with a genuine problem of a price-fixing culture, which erodes consumer trust. We are now discovering that the bread scandal is about more than just bread. These revelations are making Canada a less appealing place to invest. Executives at Aldi and Lidl can read the headlines. Instead of granting immunity to executives or waiting for companies to confess, it is time to investigate and pursue legal action against companies that choose to violate the law. In the United States, engaging in collusion can result in imprisonment. It’s that simple.