Why Robots Still Fall Short on Warehouse Complexity

The machines can load and unload trucks, move goods and do other repetitive tasks but are stymied by some, like picking items from a pile.

Robots at a DHL facility in Columbus, Ohio.

In the outbound dock of an Amazon warehouse near Nashville, a robotic arm named Cardinal on a recent day stacked packages, Tetris-style, into six-and-a-half-foot-high carts. Then Proteus, an autonomous platform, moved the carts to the loading bay, flashing electronic eyes designed to make the robot more appealing to human colleagues.

As robots become more capable, they are performing an increasing number of tasks in warehouses and delivery centers with varying degrees of aptitude and speed. Machines can load and unload trucks. They can place goods on pallets and take them off. Robots can shift items around in inventory, pick up packages and move goods on warehouse floors. And they can do all this without a human minder guiding their every move.

Yet, even though robots are starting to take over some repetitive and cumbersome jobs, there are still many tasks they are not good at, making it difficult to know when or if robots will be able to fully automate this industry.

Despite the rise in automation, warehouses remain big employers of humans. Federal data show that nearly 1.8 million people work in this corner of the supply chain. While that number is down 9 percent from its peak in 2022, when logistics companies went on a hiring spree to handle the pandemic e-commerce boom, it is still up more than 30 percent since early 2020.

A Cardinal robot selecting packages and placing them into the appropriate cart at an Amazon warehouse near Nashville.

There are many crucial, simple tasks that humans are far better at. They can reach into a container of many items and move some out the way to extract the piece they want, a task industry officials refer to as picking. Robotics engineers struggle to say when their creations will be able to do that fast enough to be viable replacements for human workers.

Artificial intelligence companies like OpenAI have served up impressive services that can quickly produce writing, images and videos that can seem to be the work of skilled professionals. But in warehouses brimming with the wares of the modern economy, advances in automation have been slower. There, robots often struggle to master skills most humans can do without much trouble.

Sparrow, one of Amazon’s most advanced robotic arms, performs “top-picking,” taking the item at or near the top of a container. Amazon says that Sparrow can manipulate over 200 million items of different sizes and weights, but that it is not adept at “targeted picking” — rummaging around many items to get one that might be buried or obscured.

“That’s a really hard job,” said Tye Brady, chief technologist at Amazon Robotics. “I’m not saying it’s impossible. That’s kind of the next frontier.”

And sometimes companies find that the robots put through tests outside the lab are not ready.

A robot known as Stretch unloading packages inside a DHL truck in Columbus.

Stretch can unload boxes about twice as fast as people can, said Sally Miller, a DHL official.

There are “more that we have not adopted than ones that we have,” said Sally Miller, the global chief information officer at DHL Supply Chain, referring to robots. The DHL division she works for operates warehouses for other companies and has deployed 7,000 robots globally.

Among the rejected: an autonomous forklift capable of stacking boxes at heights that DHL, which is based in Bonn, Germany, decided was too slow.

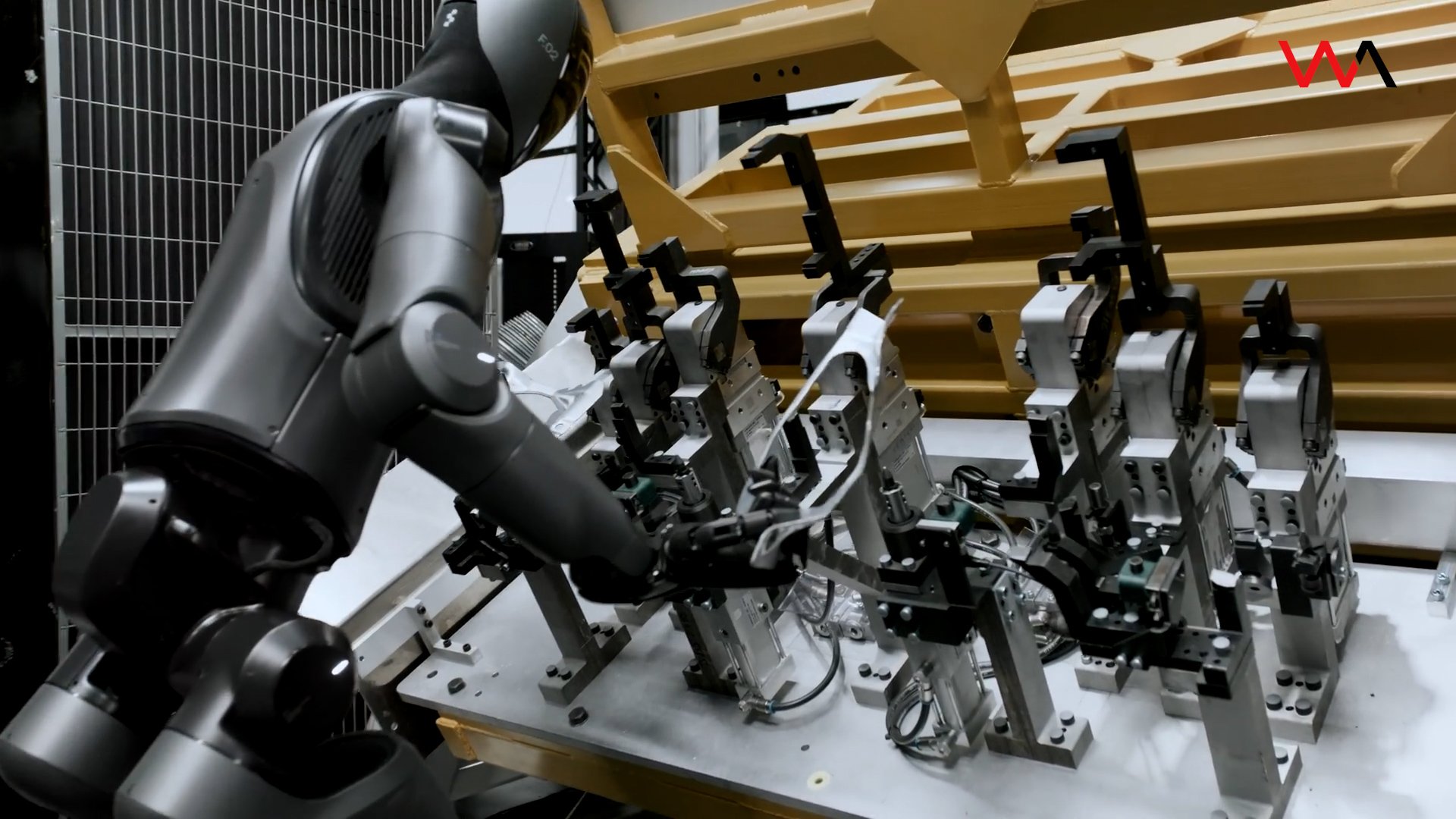

Ms. Miller said she was frustrated to see venture capital recently rushing into robots that resemble people, a category of machines known as humanoids. Such machines have long been the robotic holy grail in science fiction and in the visions of some technology executives. But to Ms. Miller, they aren’t ready for warehouse work, and she would prefer that engineers develop devices that can handle specific tasks well, quickly and affordably.

One big motivation to automate is the high turnover of warehouse employees. The work is often physically demanding and pays modest wages. Less-skilled warehouse workers earn around $16 to $17 an hour. Among the lower-paid jobs are truck unloaders, who grab boxes and move them onto conveyor systems.

That job can now be done with a robotic arm called Stretch, developed by Boston Dynamics, an automation company.

A Stretch working at an inbound dock of a DHL-run facility in Columbus, Ohio, recently reached deep into the back of a tightly packed truck and steadily removed boxes filled with apparel. A warehouse employee who oversees Stretch referred to it as “he” and spoke fondly of his ability to pick up dropped packages.

Loading packages at the warehouse near Nashville. Amazon’s overall human work force outnumbers its robots by two to one.

Ms. Miller said Stretch can unload roughly twice as many boxes per hour as humans.

She declined to say how much Stretch cost, but said: “It doesn’t call in sick, and it can work for several hours. It’s a great solution.”

Stretch can do the work of four to six workers over two shifts, DHL said, and the company has moved workers whose tasks are now being done by the robot to other jobs in different parts of the warehouse.

Some executives said their aim was to have robots do all the monotonous tasks.

“Menial, mundane, repetitive tasks will be replaced by automation,” Mr. Brady of Amazon said. “That may freak people out, but it’s going to allow people to focus more on what matters.”

Amazon has over 750,000 robots in its operations. While it does not disclose a specific number for warehouse employees, the company had 1.55 million employees at the end of September, up from 800,000 in 2019. Many work in fulfillment centers.

In the outbound dock in Nashville where Cardinal and Proteus operate, there were still scores of employees at work. But Amazon did not say how many people worked in the bay before the introduction of the two robots and how many work there today.

A worker charging Proteus robots at the Amazon warehouse. Proteus, an autonomous platform, uses sensors to avoid objects in its path.

Amazon says deploying robots creates new jobs that involve overseeing and maintaining the machines. But the number of such workers does not appear to be large. On a recent tour of the company’s Nashville facility, a manager said there were around 100 such jobs, out of 2,500 people at the center. An Amazon spokesman said such facilities typically had 200 robot maintenance employees.

Amazon’s robots do seem to be helping it process more parcels with fewer employees.

Mr. Brady said a new Amazon warehouse in Shreveport, La., using its latest technology, including an automated inventory management system called Sequoia, appeared capable of processing packages 25 percent faster and 25 percent more cheaply than the one in Nashville. Like Nashville, Shreveport will have 2,500 employees.

The structured, predictable environment of a warehouse makes it easier for robots to operate. Devising a robot that can find its own way around a warehouse at relatively slow speeds is easier than building autonomous cars that have to navigate ever-changing city streets.

Ms. Miller said robotic devices reduced the amount of walking that workers had to do.

At DHL’s delivery center in Columbus, bin-carrying robots called Locus had no trouble sidling up to human pickers, who handed pieces of apparel to the machines, which transported them to the packaging station. Ms. Miller said Locus and similar devices were designed to reduce the amount of walking pickers do.

Robotics engineers say A.I. technologies have helped them make progress.

Marc Segura, president of the robotics division at the Swiss company ABB, said a client wanted to enable a goods-sorting robot to identify and avoid bulky items. Using A.I., the machine taught itself what such items looked like and now avoids them, he said.

Sometimes the advances don’t rely on cutting-edge technologies.

Fox Robotics makes autonomous forklifts that can unload pallets from trucks and place them on the loading dock floor.

Customers wanted the forklifts to be able to place pallets on rolling conveyors so they could be moved more quickly to their destination. But the pallet created a blind spot that prevented the forklift from seeing whether a conveyor had enough open space. On its latest machines, the company overcame that problem by adding more sensors, effectively expanding the forklift’s vision.

“Once we had those sensors, doing the actual placing on conveyor was trivial,” said Peter Anderson-Sprecher, chief technology officer and a co-founder of Fox Robotics.