Amazon Fulfillment Centers Drive Local Economic Growth, Study Finds

Amazon Warehouses Benefit Local Economies, Study Finds

A new study by economist Evan Cunningham reveals that Amazon's fulfillment centers positively impact local economies by increasing employment rates, wages, and home values in metro areas. While rents and utility costs also rise due to higher demand, the overall benefits—especially for non-college workers—outweigh the drawbacks. The study highlights Amazon's role in reshaping labor markets and the nuanced effects of state and local subsidies that often accompany its expansion.

The newly published paper found that Amazon's entry in a metro area led to increases in wages, jobs, and home values.

It is often taken as a given that corporate retail giants like Amazon are "killing Main Street."

"Amazon is a retail monopoly that threatens every corner of our nation's economy," United Food and Commercial Workers International Union president Marc Perrone said in 2020. "Left unchecked, it will eradicate jobs, small businesses, and countless American retailers across the nation."

When the company announced that it would build a corporate headquarters in a New York City suburb, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D–N.Y.) complained it would displace the existing population. "Shuffling working class people out of a community does not improve their quality of life," she tweeted.

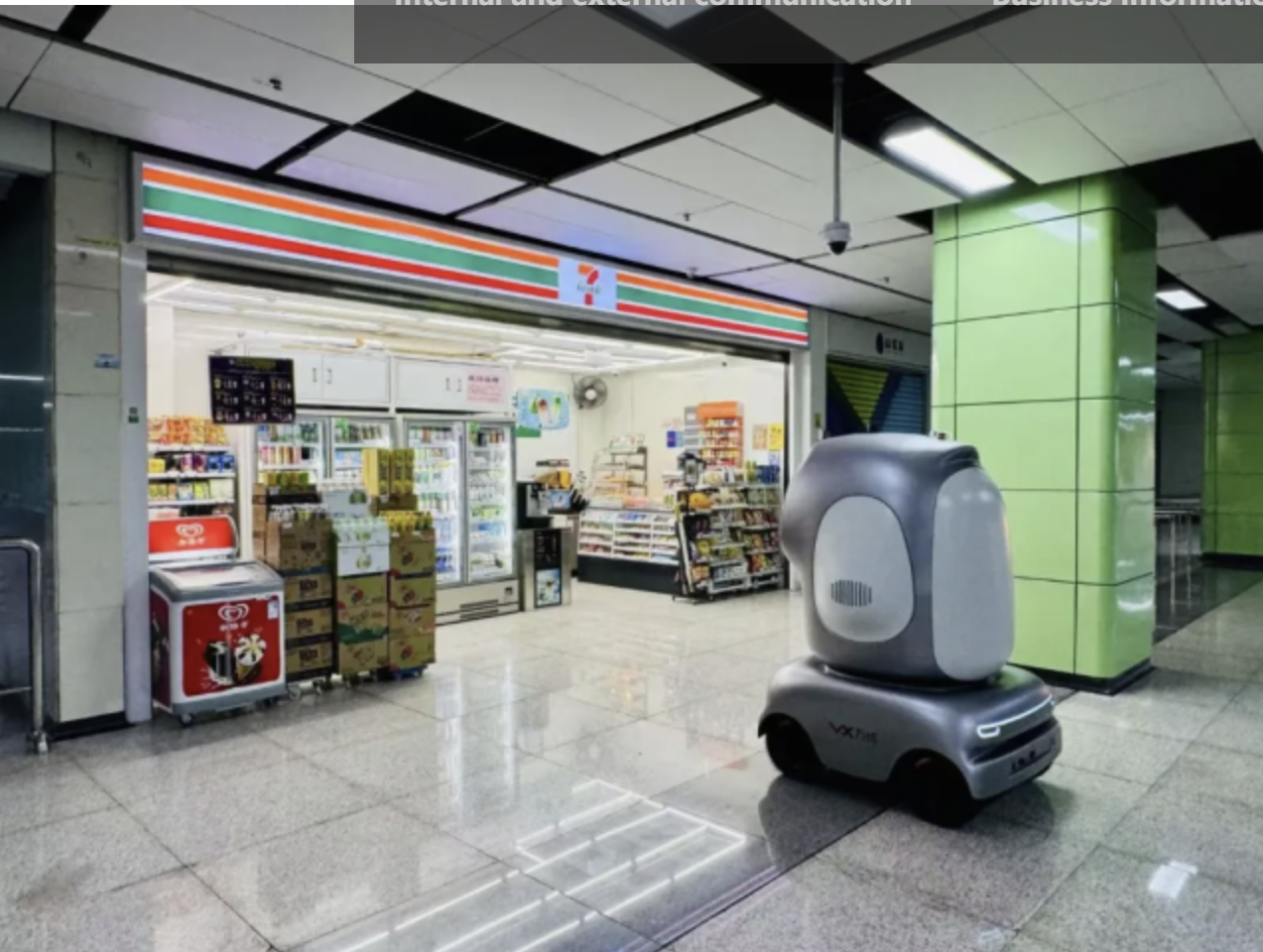

In a newly-released research paper, Evan Cunningham, a Ph.D candidate in Economics at the University of Minnesota, studied the effects of Amazon's continued spread across the country—growing from just a handful of warehouses, or "fulfillment centers," in 2010, to more than 1,300 today in the U.S. alone. On balance, it turns out that Amazon warehouses provide a net positive to local economies.

"I find Amazon's entry in a metro [area] increases the total employment rate by 1.0 percentage points and average wages by 0.7 percent," Cunningham writes. "The composition of employment shifts from retail and wholesale trade to warehousing and tradeable services, primarily driven by younger workers. Employment gains are concentrated among non-college workers."

There are also some drawbacks, though it largely depends on your perspective. "Amazon's entry increases rents by 1.1 percent and the cost of utilities by 6.0 percent," while "average home values increase by 5.6 percent." Higher rents and utility rates may not sound particularly appealing, but Cunningham notes that this is a result of higher housing demand: "The average worker is willing to pay $329 per year to live in a large U.S. city after Amazon's entry, relative to a counterfactual U.S. economy where Amazon did not expand. This increase was primarily driven by rising home values, implying the benefits accrued to home owners."

Indeed, as with any increase in demand, costs rise without an equal increase in supply; when a lot of people want to move to one place, housing costs will increase as a result.

Cunningham also examines the influence and effect of state and local subsidies. In a 2019 working paper, economist Timothy J. Bartik of the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research calculated that states spend nearly $60 billion per year on "placed-based jobs policies," designed to increase the number of jobs in a particular location. Of that total, the overwhelming majority—$46.3 billion—take the form of cash or tax incentives for businesses.

Amazon is no stranger to government incentives—indeed, Cunningham deems it "arguably the modern poster child of state/local business incentives."

"According to Amazon, fulfillment centers are engines of job creation, often hiring thousands of workers," Cunningham writes. "Based on this premise, state and local governments have provided nearly $2.6 billion in subsidies, grants, and tax rebates….In an average metro, state and local governments combined spend roughly $79 per adult per year on corporate subsidies," totaling "upwards of $60 million" in an average metro area.

"Subsidies represent a very small share (about 1 percent) of state and local budgets," Cunningham tells Reason via email. "This means if a large employer (like Amazon) leads to a broad increase in economic activity, the increase in local tax revenue will more than cover the cost of the subsidy. So, the fact that cities are providing incentives to Amazon has a very limited impact on the average worker."

"Now, I'm not arguing that subsidies are always the best use of those taxpayer dollars," he adds. "If city leaders knew Amazon would move to their city regardless of any subsidy, then the money could be put to better use. On the other hand, if the subsidy was the difference between Amazon coming to your city or not, my results suggest it is on average worth it."

Bartik reached a similar conclusion in his 2019 paper: "Should policymakers seek to increase jobs in particular local labor markets? Yes, but only if these policies are well targeted and designed," he wrote. "Encouraging job growth in distressed places can cause persistent gains in employment-to-population ratios. But our current place-based jobs policies, under which state and local governments provide long-term tax incentives to megacorporations, are poorly targeted and designed."

Indeed, even by states' own metrics, these enormous expenditures are rarely worth it, as states spend billions of dollars and claim a few hundred thousand jobs, as the broader economy adds millions of jobs.

And to Bartik's point, it's hard to imagine many corporations more "mega" than Amazon, a company worth more than $2.4 trillion and employs more Americans than any other company but Wal-Mart. (Sadly, each pales in comparison to the federal government, which employs 2.95 million people.)

Cunningham derived his $2.6 billion total from the subsidy watchdog Good Jobs First, and he intentionally counted only state and local incentives for fulfillment centers; a 2022 Good Jobs First report found that overall, the company had received "more than $4.18 billion in the United States alone" in total government incentives.

In fact, when Amazon first announced its plans to build a second corporate headquarters, it did so by encouraging cities to compete over who would offer the best deal. After 238 cities applied, putting forward the most generous offers of taxpayer money they could muster, Amazon chose to build in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. (Opposition from activists, including Ocasio-Cortez, scuttled its plans to simultaneously build a location near New York City.)